London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) studies the social sciences in their broadest sense, with an academic profile spanning a wide range of disciplines, from economics,

politics and law, to sociology, information systems and accounting and finance.

The School has an outstanding reputation for academic excellence and is one of the most international universities in the world. Its study of social, economic and political problems focuses on the different perspectives and experiences of most countries. From its foundation LSE has aimed to be a laboratory of the social sciences, a place where ideas are developed, analysed, evaluated and disseminated around the globe.

Ipsos MORI is the second largest market research organisation in the United Kingdom, formed by a merger of Ipsos UK and MORI, two of Britain’s leading survey companies, in October 2005.

Ipsos MORI conduct surveys for a wide range of major organisations as well as other market research agencies.

Needs for accessible housing

Of households in England that include a disabled adult at least 1.8 million have an identified need for accessible housing, of whom 580,000 are working age.

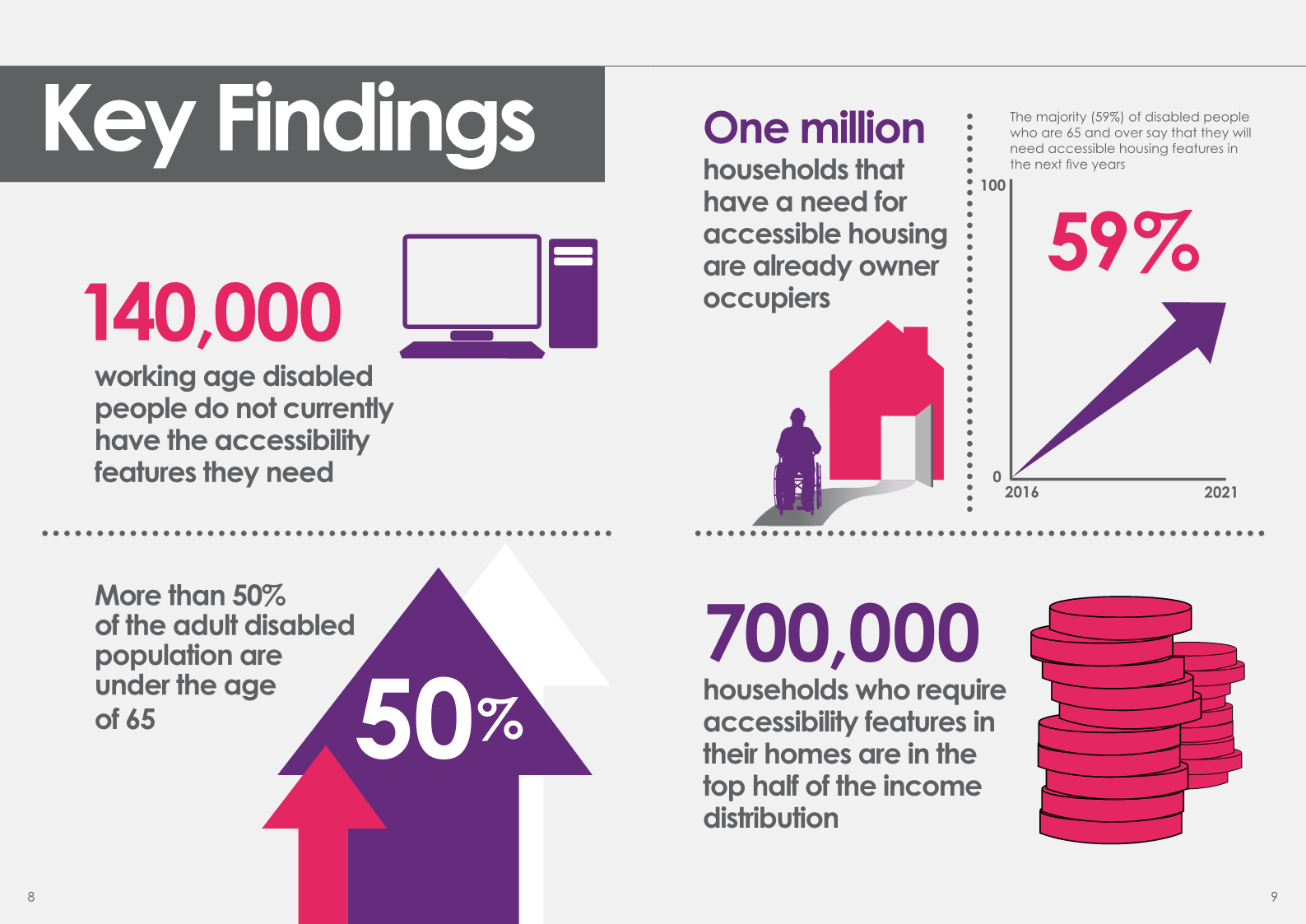

At least 1 in 6 households that need accessible homes do not currently have all the accessibility features they need – equating to 300,000 households, including 140,000 of working age. This means that working age households are less likely to have the features they need than older households.

The hidden market in numbers

One million households that have a need for accessible housing are already owner-occupiers and of these some 230,000 are of working age.

Significant numbers of people with needs for accessible features also have the means to consider the purchase of a home.

Amongst households with an identified need for accessible housing,

39% (700,000) have incomes in the top half of the income distribution of the population as a whole. In addition, 55% of owner occupiers living in a

household including a disabled person and 33% of working age households containing a disabled person have incomes above this level.

However, there is already a shortage of accessible housing in the UK and time after time house building targets have not been met. The slow rate of building in the UK may become even worse after the referendum: shares

in house-builders have slumped badly as a result of the uncertainty caused by the vote to leave.

360,000 households containing a disabled person have savings of £12,000 or more. 1 in 4 households needing accessible housing (480,000) have incomes above the median income after housing costs of all owner occupier households (£448 per week).

Disabled people are significantly more likely to be dissatisfied with their current home than non-disabled people – 14% say they are dissatisfied

compared to 8% of non-disabled people. Satisfaction levels are lowest among disabled people under 45 and those currently renting from a private landlord6.

Motivation to buy or move

A majority of the public would like to change something about their home, most commonly achieving more space or more rooms, gardens or parking. Disabled people are more likely to mention an internal change to their home, most commonly addition of or improvements to a downstairs toilet or bathroom.

In talking directly with people with a need for accessible features in their home the LSE research found that some people choose to cope as best they can without seeking to make changes, some pay for adaptations themselves (assuming that there is too little or no resources available from local authorities), and some consider a change of tenure their best option.

Whilst some would consider a house move to address their access needs, changing tenure or moving house would be more likely as part of a wider

life change such as family expansion or downsizing at retirement. In this sense the market for accessible homes mirrors the market in general. However, older people or those who are carers are more likely than the general population to think of moving.

What distinguishes this market segment is their specific requirements for features that make it possible for them to buy with the confidence that their new home will meet their needs into the future. Many also found the proximity of family and friends – their support network – an essential factor in choice of location.

The survey work also found that a number of people of all tenures see a move to social rented housing as a likely future option, that would meet their accessibility needs as they grow older.

The Ipsos MORI survey found that regardless of current housing situation the public in general do acknowledge their potential future need for accessible housing features to some degree.

The majority (59%) of disabled people who are 65 and over say that they will need accessible housing features in the next five years, with 46% of all disabled people and 20% of the general public saying the same.

Of people with caring responsibilities, 47% say that the person they care for will need accessible housing features within the next five years or so.

Conclusion and Recommendations:

The growing number of disabled people, queues of first time buyers and not least our increasing population of older people demand that we pay attention to the way that our new homes are designed and demonstrate a clear market for accessible homes.

Not to address this now, as the UK ramps up its house building efforts, risks replacing one housing crisis with a different one in years to come. The findings of this research programme point to four main recommendations:

1. Developers and their marketing teams should look again at their target markets and products. Are they missing out on the significant market of people that have or anticipate having needs for accessible features in their home and have the financial means to buy? Is there an opportunity to deliver more of what the public like by providing more homes with inclusive features such as downstairs bathrooms and level entrances?

2. Developers, planners, and health and social care commissioners should take note of the overwhelming desire of the general public to maintain independence in mainstream housing as they age and/or develop needs for care and support. We need to ensure that the homes of the future enable people to age in place, or have genuine choice to move to a home that is designed and built to support their ongoing independence – not only for the sake of the household but to minimise public spending on the alternative.

3. Government departments should collaborate to investigate the correlation between unmet need for accessible housing and being out of work. If we are serious about enabling more disabled people to enter or re-enter the work place it is critical that we understand the fundamental role that appropriate housing plays, and plan accordingly to provide genuine, viable options.

4. Improving our data resources is critical if we are to respond effectively to the housing needs of the nation. Disregarding the needs of families with disabled children is to discount an important segment of the market, whilst not being able to match identified needs with the official housing standards is an enormous missed opportunity to create accurate, evidence based plans.